As we approach the end of year exams, many students face one of the biggest minefields when it coming to learning Chinese – composition writing. And while compo is no longer the highest weightage section (Oral is higher), it’s still quite often the key difference between an A vs B, or AL1 vs AL2. In this post, we provide a quick introduction on why the traditional approach to composition involves so much drilling, and introduce a new, reading-based approach to practising compo writing.

REFRESHER ON PSLE CHINESE BREAKDOWN

Let’s first look at the marking rubric for Normal Chinese. Students can get a maximum score of 200 for PSLE Chinese, of which composition comprises 40 marks (20%). Students can attempt either Picture Composition (看图作文) or Topical Composition (命题作文), and we typically recommend the former as it is easier to visualise and harder to “go out of point” (usually means failing grade).

Compo marks are evenly divided between content (内容) and language expression(表达和结构).

Content is based on how well a student has described each picture, whether the conclusion and reflection makes sense, and whether the essay is “out of point”. Most content marks are lost in the conclusion and reflection due to lack of creativity or experience, or when students lack the vocabulary to correctly describe each picture.

Language expression refers to both the essay structure (开头结尾), proper sentence structure as well as how descriptive the language used, which highlights the importance of learning good phrases (好词佳句). Marks are also deducted for mistakes in writing characters.

THE TRADITIONAL APPROACH TO COMPOSITION

One of the problems with the PSLE format is that in order to differentiate great from good students, there will always be “killer” questions or sections (remember last year’s PSLE Math “Helen and Ivan coins” question). For Chinese, one of the differentiating sections is composition, where you cannot get extremely high marks without using tons of flowery language (成语,比喻句,俗语), even if such writing is actually overly-stilted in real-life.

That’s why for decades, the Singaporean approach towards teaching Chinese composition has been geared towards memorisation. Memorise vocab, openings, and endings, and pray for a relevant topic so you can regurgitate everything.

There are advantages to this traditional approach – it is extremely aligned with the exam format and is quickly applicable. Moreover, it’s effective as students can be taught a relatively large amount of vocabulary in a short period of time. Even at KidStartNow, we utilise the traditional approach during our weekly enrichment lessons. However, we are aware of the problems of overusing such an approach.

WHAT IS THE DOWNSIDE?

From a pure MOE examination standpoint, learning Chinese is a 12-year marathon not a sprint that ends after the upcoming exam or Primary Six. The teacher-led, traditional approach to composition typically has low levels of interaction between teacher and students. Besides being un-interactive, students also have less opportunity for creativity and independent thought, important qualities for a rapidly changing world.

Moreover, endless memorisation will cause students to hate writing, and by association, Chinese in the long-term. When kids dislike Chinese, they are trapped in a vicious cycle of not wanting to practise, leading them to become worse, and looping back to more loss of interest in Chinese.

READING-BASED APPROACH

During the school holidays, a reading-based approach that teaches vocabulary & writing is a far more enjoyable, sustainable and long-term effective way to get better at writing. If you can get your child to read 10 minutes a day for the next 2 months during the holidays, they will see big improvements in language expression, reading speed (important for comprehension), and vocab.

This is backed by research that shows that children can increase their vocabulary substantially through incidental learning, where students encounter new words from reading, even when they do not receive explicit explanation of these new words. In particular, “repeated encounters with a word, provided through extensive reading, would lead to the long-term, cumulative effect of vocabulary growth.”

Picture composition and reading go hand in hand

There are other benefits to reading as well. As mentioned above, we typically recommend student attempt the Picture Composition topic when writing composition as it’s harder to accidentally go “out of point”, but it also has its challenges, like writing a coherent story.

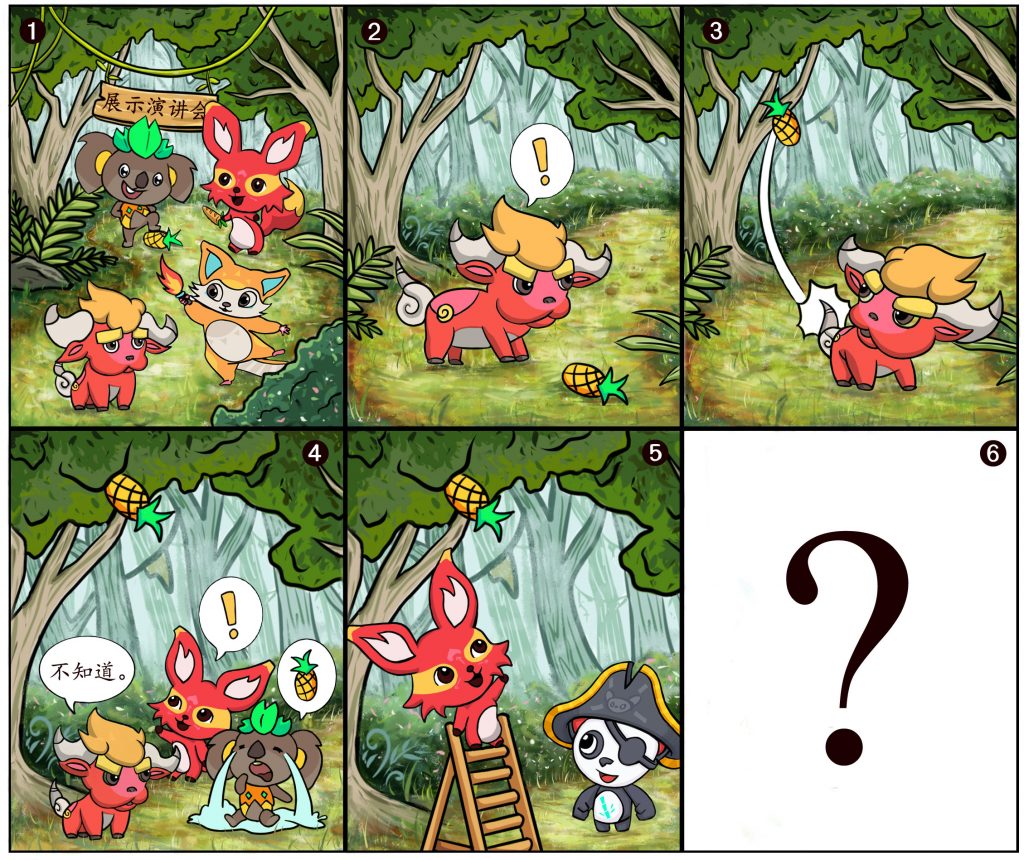

Regardless of whether you are doing a 4 or 6 picture essay, the final picture is always blank and is meant to test if students are able to craft a logical conclusion based on the previous pictures.

While this seems easy for adults, this is actually a common area of weakness for students, and many lose important marks from inconsistent conclusions. Part of this is due to lack of familiarity with exam techniques, as primary school compo tend to be moralistic in nature, and it’s easy to score as long you are familiar with the common themes (e.g. learning from one’s mistakes, importance of honesty, etc). But part of the problem is as students typically don’t read Chinese stories, they aren’t very comfortable with narrating a story to its logical ending.

But I can’t get my child to read

Parents all know the importance of reading, but the problem is most primary school children much rather read English books.

After all, primary school children decide what books they want to read, and most find English books far easier to read and more interesting. And even if they wanted to read Chinese stories, when they encounter words they can neither pronounce nor understand, most Singaporean parents are unable to help, and checking a dictionary is tiresome.

Enter animated stories with read-aloud (see below for an example). The idea behind animated stories is that the content is engaging to kids while exposing children to a wide range of vocabulary. Even if they don’t fully understand all the words, the combination of animation and read-aloud helps students naturally build up their foundation. Unlike adults, children learn languages like a sponge, and can easily broaden their Chinese vocabulary just by being exposed to animated stories.

It’s much easier to convince a child to read an animated story over a traditional book if they are reluctant Chinese readers, and as they get more comfortable with Chinese, you can then introduce more traditional books in the future.

DECEMBER HOLIDAY CAMPS

As mentioned, if you can get your child to read 10 minutes a day for the next 2 months during the holidays, they will see big improvements in language expression, reading speed (important for comprehension), and vocab. But if you don’t have the time to regularly help your children with reading or compo, you can consider KidStartNow’s 4-day Pet Battle Compo camps (P2-P5) held during the Dec holidays at our Bedok branch.

Over 4 days, your child will practise compo, learn new vocab and master key writing skills through fun games, engaging stories and exciting team based activities set in our Pet Battle universe. In addition, we have created a brand new set of animated stories that will help your child practise writing while drawing them into a fun adventure:

After 500 years of peace, the Dark Wizard returns to Boshiland, plunging it in darkness and corrupting the pets there. One last hope remains: a brave child who can free the pets by answering Chinese question. Will your child be able to rescue the pets and defeat the Dark Wizard?

We have been running these camps since 2018, with extremely positive feedback from parents and students. If you are looking to improve your child’s compo skills while building vocabulary foundation through idioms, metaphors and good vocabulary, please call/whatsapp us at +65-9820-7272 or click this link.

Comments are closed